Escaping into the wild can be challenging on this crowded isle, but probably the wildest, most untouched landscapes left in Britain are underground. Even caves attract too many visitors though and – like when summiting Everest – there can be queues but cave-diver avoid all that.

I was living in Devon and heard of a cave, Pridhamsleigh Cavern, that contained a deep lake; blind white eels were rumoured to live there, and weird animals interested me. Someone was said to have dived to 130ft/40m and not reached the bottom; 130ft is the very limit of recreational SCUBA diving. Any deeper and you need to use helium.

Cave divers are nervous of deep dives, but I knew about nitrogen narcosis, decompression and the bends. But I was in a quandary. I’d been taught never to dive alone whereas cave-divers often do. Flooded subterranean passages can be tiny and, as there is little chance of rescue if things go wrong, having a buddy isn’t likely to help. Nor does a life jacket. They get snagged on rocks. Maybe that’s why a third of cave-divers die pursuing their sport.

I’d recruited Richard to explore with me. He was a cave diver with an intrepid reputation and was enthusiastic about the prospect of discovering new depths. Saturday came and five of us assembled in the unsalubrious mire trapped at the bottom of a small limestone outcrop. The yawning entrance of Pridhamsleigh Cavern exhaled cool air. We had a lot of kit. We’d needed helmets, lights, back up lights, fins, masks, demand valves, knives and a line on a spool to find our way home. We also needed plenty of air – to allow for decompression time. I’d dive with two waste-slung aqualungs and 8lb weight belt. Richard brought hugely heavy twin 60 cu ft air cylinders and wore a bulky bright red Unisuit. This is the kind people use for diving in the Arctic and needed 30lb of lead to sink him. Richard announced that he’d super-heat in his Unisuit if he carried his aqualungs or the lead.

Devon caves are rabbit-warrens of small passages. They began beneath the water table and, over the eons, limestone dissolved and passages formed. Tunnels seem carved out of reddish clay. This clung onto the cylinders so we had to unstick them every time we wanted to move forward. I felt grateful that my wet-suit was so well-ventilated by rips at the armpits, elbows, arse and knees.

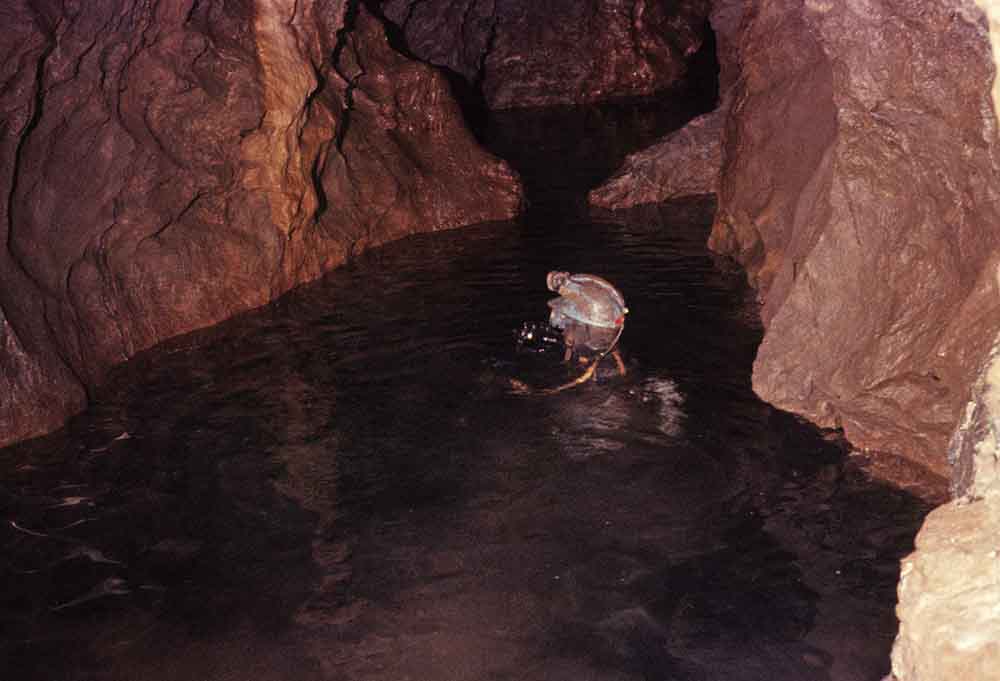

|

| Getting diving equipment into place can be hard work |

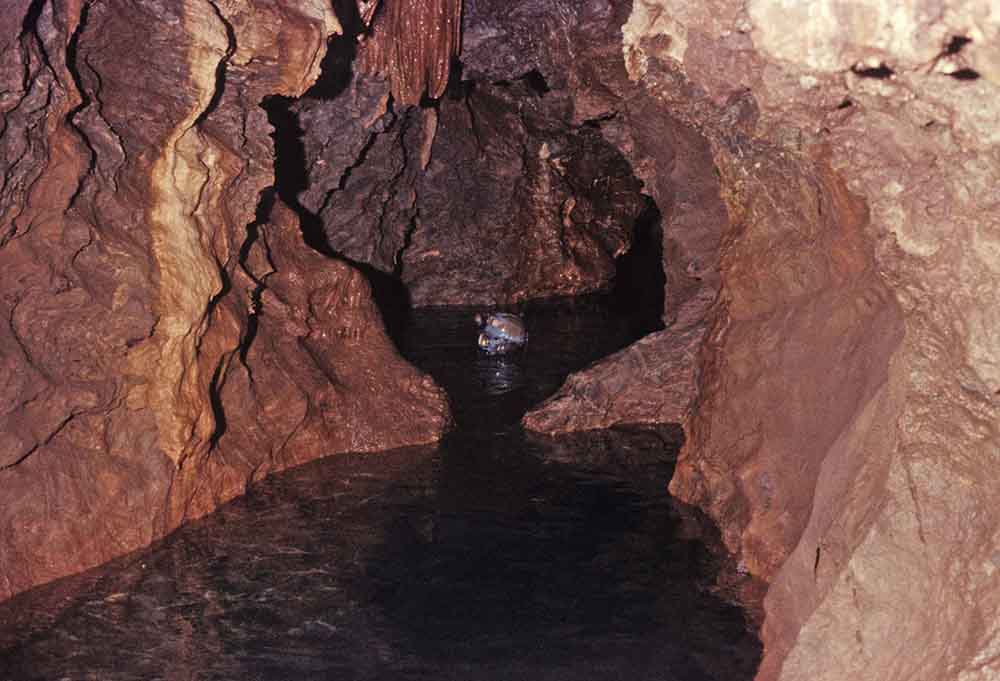

|

| The "Little Man" of Baker's Pit in Devon shows how limestone can surprise |

It took us an hour to crawl and man-handle the cumbersome gear through passages some of which were barely a foot high. When we finally arrived at the clear blue water of the little underground lake, it seemed almost miraculous. It was a mere 10ft wide but looked cool and inviting. I’d already dived here, but Richard was keen to lead. He kitted up and slipped into the water, muddying it. I followed. The icy cold took my breath away. I steadied my breathing and cruised 50ft to the other end of the lake. There a thick fixed guide rope, which explorers before us had installed, ran from a bolt and disappeared into deep blue nothingness.

|

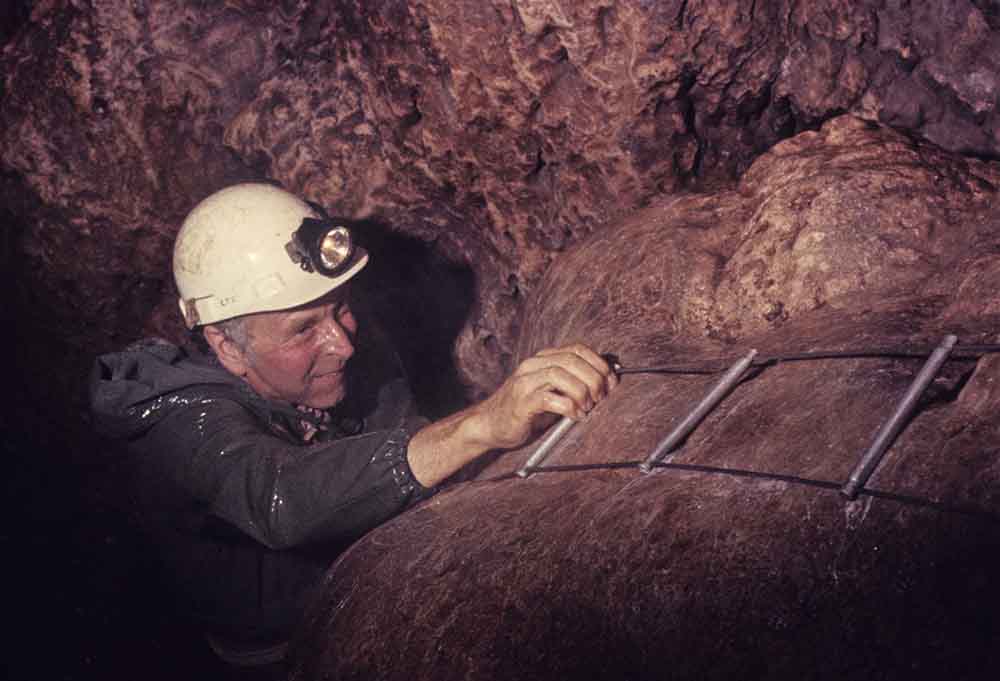

| Kitting up for a first solo dive with the help of sherpa John Dukes |

|

| Muddying the pristine lake in Pridhamsleigh Cavern |

|

| Nervously pushing into deep water |

|

| Ready to submerge |

Rich gave the OK sign and submerged. I glanced back to the watching lights. I bent in the middle. Fins up and pulled myself head first down the rope. Richard had churned up a lot of mud so I could only see 12 inches in front of me. Little flakes of luminously white limestone floated by like giant snowflakes. Mesmerising. The world was silent, except for rhythmic bubbling breathing.

Eighty feet (25m) down this narrow rift in the limestone, the rope divided but Richard rushed on deeper. At about 100ft/30m, his head hit the bottom. The small impact made mud swirl around him. His arms were still working to pull him deeper. I got the giggles. My mask flooded. He was still head down by the time I’d cleared out the water and could see again, but he had stopped moving. There was a long pause while his brain registered he must manoeuvre himself so that he was head up. Slowly, he rose out of the mud and I led us up and took the horizontal rope. Suddenly – as if we’ve come through a portal – we were in an enormous underwater chamber. I couldn’t see walls or floor. Spellbound, I watched my bubbles hurtling upwards. I couldn’t see where they surfaced, or if they surfaced. The chamber was dazzlingly sky-blue and vast. I was moved to tears, it was so awesome. I was aware my brain was scrambled and working so, so slowly. I was "narcked" but I had experienced nitrogen narcosis and thought I could accommodate it. Rich was beside me. His eyes were huge. It looked like he would panic if anything – anything at all – went wrong. I wasn't sure he'd been this deep before.

Rich tied his line onto the thick fixed rope, dropped down and disappeared into the muddy depths. Gingerly I followed with one hand on his line. The visibility had gone from about 30ft to six inches. Soon I bumped into a soft red object that gesticulated at me. He gestured for me to go back. We collided again and again. Buoyancy – his too much, mine too little – and poor visibility made this tough.

We returned to the fixed rope. Visibility was good here: good enough to see a red Michelin man hurtling upwards while he tried to push his buttons to bleed air and reduce his buoyancy. When he managed to get back down to me he looked even more fearful than before. He raised two fingers and disappeared through the portal.

I followed, rattling and bumping back up to the surface. I’d assumed he was returning for a piece of equipment but he’d had enough. He’d decided the dive was over but I had plenty of air left and wasn’t ready to go home yet. I took Richard’s spool and line and submerged again. Down the narrow rift I went, and into the awesome chamber. Slightly to my surprise, I managed to tie a bowline first time, which is something I often struggle with on the surface and without nitrogen narcosis.

I let myself sink down, getting rapidly heavier as I went deeper. My depth gauge showed 80ft, 100ft, 110ft (34m deep).

I landed heavily and raised a cloud of brown mud. The visibility was a few inches. With the air so compressed in my body and my wet suit, I was too heavy. I hadn’t thought about this. In order to do a proper survey of this vast chamber, I needed to hover above the mud. On previous deep dives in the sea I’d used my life jacket to control buoyancy but that day I wasn’t wearing one.

I tried to swim but kept sinking to grovel and crawl on the muddy bottom. My air is going fast. I moved forward until I found the wall of the chamber by hitting it with my helmet. For a while I followed the line of the wall round. I had one hand on the line, the other out ahead to feel my way. Feel for new tunnels. The cold had made my hands clumsy. I was scared – really scared of letting go of the line that would show me the way home. Then I realised I was kneeling, holding onto the line with both hands. That was going to get me nowhere.

I went to move on. Something was stopping me. Now I was really scared. I struggled upright so I was kneeling. Eventually I realised I was tangled in my safety line. I could cut it with my knife but then I’d lose the guide to bring me home. I told myself to calm down and sort it out. It took a while but it wasn’t so difficult.

Onward, I repeatedly bumped into solid rock. I had no idea how far round the chamber I’d gone. I didn’t have a sense of the way back any more. I thought about what would happen if my bowline came untied and I couldn’t find my way back. I was shivering and miserable and oh so lonely. But I had come all this way and my friends had helped carry all my gear so that I could look for submerged passages running from this chamber. I was pretty sure by now that there were none. I considered that there could be a pot hole in the floor going much deeper. I wasn’t going to find it like this.

I stopped. Got kneeling again. Wrestled to see how much air remained. Not much. My thinking was as sluggish as my movements but hadn’t forgotten that cave divers should finish a dive with plenty of air left – leaving a big margin of safety. I struggled to stand, tripping on a fin as I did. Suddenly I was seized with a feeling that I had to get out of the mud. I pushed up and began powering upwards. So heavy. My fins were small. I hadn’t thought about this either. I wished I had a life jacket help me to rise to the surface. I knew I could drop my weight-belt but that might leave me unable to get down to the portal and the way out.

I was struggling. I was out of breath. I finned harder. I began to see again. Vast agoraphobic azure.

Progress became ever easier as I rose. Soon my lungs felt full and my body buoyant – a sign I was near the surface. There! Suddenly splashing sounds and I was breathing real air again. I was in a chamber 30ft high and 80ft in diameter. Steep-sided walls meant I couldn’t climb out of the water.

‘Wow!’ I said out loud. My voice echoed eerily so I tried not to make any more sounds.

The chamber looked unfamiliar. I was sure I’d never been here before. I was sure I’d surfaced in an unknown air bell. I felt very lonely.

I looked up. To my horror there was an enormous jellyfish floating in the air high up in the chamber.

I looked again and saw that what I mistook for a jellyfish was a complex stalactite curtain hanging from the ceiling of the chamber. My headlight reflected off water droplets falling from the tentacle ends. Drip, drip. Was nitrogen narcosis making me hallucinate? I wanted to go back. I didn’t want to explore any more.

As I scanned around, light glinted back from a portable wire ladder leading to a tiny ledge 12ft/3-4m above the water. Rats! I wasn’t anywhere new. I was no intrepid explorer. I recalled talk of emergency supplies – probably just a bar of chocolate and a light – stashed here but how the hell had they managed scale that smooth rock wall to get up there and rig that ladder?

|

| Wire ladder of the kind used by cavers - this is "Jeff" Jefferson in Swildons |

I tried to take in the scene, enjoy it. I was probably the first woman to have reached this place and one of the few who had tried to explore the depths, but that didn’t make me feel any better. Shivering convulsed me. I gathered myself mentally. I cruised around the air bell to the bolt securing the fixed rope. I put my mouthpiece back in and submerged. Now I was focused only on rushing back to my friends at the lake. I slipped through the portal. Visibility dropped to a few inches again. My helmet and aqualungs rattled and banged against solid rock. The passage hadn’t seemed so small before.

I ascended carefully. Ten feet from the surface, I had to stop for five minutes to allow the nitrogen to diffuse out of my blood, to avoid the bends. I was cold. It was a long, long five minutes. I counted forwards. I counted backwards. I studied the intricacies of the water-sculptured rock. Little fossil seashells poked out of the bedding planes. I watched the mesmerising limestone snowflakes float down. I searched for the tiny blind shrimps that inhabit the cave. I prayed an eel would come by. I pondered on what strange sensory deprivation there is in caves and in diving. I tried to think of games to play but nothing took my mind away from the numbing sapping cold.

At last I could surface. It was so good to take the demand valve out of my mouth. Four lights were looking at me.

‘Okay?’

‘Great.’ My lips had turned to rubber and my mouth hardly worked.

I finned the length of the little lake. Rich had already dekitted. The others helped me out of the water. I felt so weak. I struggled to take off all the cumbersome equipment. I couldn’t feel my feet. I was shivering and silent. I was almost looking forward to the struggle out with the gear. At least it should warm me up.

An hour later, I was standing upright in the sunshine again. My feet no longer felt like stumps. Cow shit had never smelt so good. Birds were singing. Back in the world again, I was steaming, muddy and grinning.

By now I was full of my adventure and ready to do it all over again. What was more, the dive gave me credibility amongst the macho caving community and I became known as Lady Jane – an acknowledgement, I think, that although I was one of the lads, I didn’t fart and belch loudly nor did I swear (much). More importantly it reminded me that there is a lot to savour in wilderness experiences. That feeling of awe that engulfed me when I entered that vast azure space will stay with me forever, and there is also that almost indescribable, perception-shifting experience of facing a challenge that might not have been survived. It gives life a little more spice.

It had been an amazing trip but I resolved that next time I’d dive without a buddy. Then, perhaps, I’d see the eels. Or were these just a nitrogen-induced hallucination like my jellyfish?